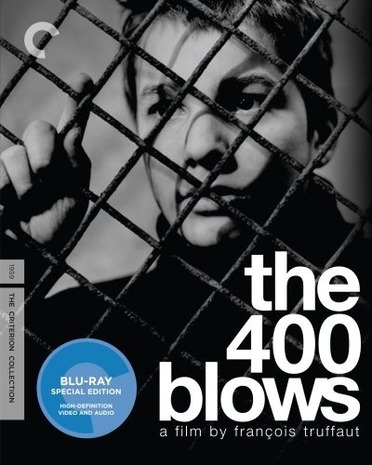

François Truffaut's debut feature, The 400 Blows earned the prize for best director at the Cannes International Film Festival in 1959. In an instant its young maker was on the map of international film culture—and smoothing the way for such New Wave colleagues as Jean-luc Godard and Eric Rohmer, already immersed in cutting-edge projects of their own.

Like the other New Wave filmmakers, Truffaut cultivated his key ideas writing articles for Cahiers de Cinema, the literate film magazine edited by Andre Bazin, who encouraged his critics to pursue their convictions often far from his own distinctive blend of aesthetic and philosophical concerns. Truffaut was the most aggressive writer of the group, fiercely criticizing French cinema's "tradition of quality" while formulating the politique des auteurs that saw strongly creative directors as the primary authors of their films.

The 400 Blows abounds with the spirit of personal filmmaking that Truffaut had celebrated as a critic. The hero, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), is a thinly fictionalized version of the auteur himself, and Truffaut later revealed that he boosted the intensity of the 15-year-old actor's performance by joining him in a private conspiracy against the rest of the cast and crew. Master cinematographer Henri Decae shot the picture in real Paris locations, and Truffaut never hesitated to stray from the story for moments of poignantly conveyed emotional detail. One such sequence comes when Antoine rides in an amusement-park centrifuge, twisting his body into wry contortions that express his rather weak impulse to rebel against society's constricting norms. Another comes at the end of the film, when Truffaut's camera escapes from a detention camp with Antoine, tracking on and on as he runs breathlessly toward nowhere, then zooming toward his face to capture a freeze-frame portrait of existential angst that is arguably the most powerful single moment in New Wave cinema.

Truffaut and Leaud continued Antoine's adventures in four more films, ending the series with Love on the Run in 1979, four years before Truffaut's untimely death. While these sequels have their charm, The 400 Blows remains unsurpassed as a distillation of the New Wave's most exuberant creative instincts. —David Sterritt (1001)

Francois Truffaut's first feature was this 1959 portrait of Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a boy who turns to petty crime in the face of neglect at home and hard times at a reform school. Somewhat autobiographical for its director, the film helped usher in the heady spirit of the French New Wave, and introduced the Doinel character, who became a fixture in Truffaut's movies over the years. Poignant, exhilarating, and fun (there's a parade of cameo appearances from some of the essential icons and directors from the movement), this film is an important classic. "—Tom Keogh"

François Truffaut’s first feature, The 400 Blows (Les Quatre cents coups), is also his most personal. Told through the eyes of Truffaut’s life-long cinematic counterpart, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), The 400 Blows sensitively recreates the trials of Truffaut’s own difficult childhood, unsentimentally portraying aloof parents, oppressive teachers, petty crime, and a friendship that would last a lifetime. The film marks Truffaut’s passage from leading critic of the French New Wave to his emergence as one of Europe’s most brilliant auteurs.

THE 400 BLOWS

By Annette Insdorf

François Truffaut’s first feature, The 400 Blows (Les Quatre cents coups), was more than a semi-autobiographical film; it was also an elaboration of what the French New Wave directors would embrace as the caméra-stylo (camera-as-pen) whose écriture (writing style) could express the filmmaker as personally as a novelist’s pen. It is one of the supreme examples of “cinema in the first person singular.” In telling the story of the young outcast Antoine Doinel, Truffaut was moving both backward and forward in time—recalling his own experience while forging a filmic language that would grow more sophisticated throughout the ‘60s.

The 400 Blows (whose French title comes from the idiom, faire les quatre cents coups—“to raise hell”) is rooted in Truffaut’s childhood. Born in Paris in 1932, he spent his first years with a wet nurse and then his grandmother, as his parents had little to do with him. When his grandmother died, he returned home at the age of eight. An only child whose mother insisted that he make himself silent and invisible, he took refuge in reading and later in the cinema.

Like Antoine, Truffaut found a substitute home in the movie theater: He would either sneak in through the exit doors and lavatory windows, or steal money to pay for a seat. In The 400 Blows, Antoine and René reenact the delinquency and cinemania of the young Truffaut and Robert Lachenay (who was an assistant on The 400 Blows). Their touching friendship is captured in René’s unsuccessful attempt to visit Antoine at reform school.

And like Antoine, Truffaut ran away from home at the age of eleven, after inventing an outrageous excuse for his hooky-playing. Instead of Antoine’s lie about his mother’s death, Truffaut told the teacher that his father had been arrested by the Germans. The recent revelation that Truffaut’s biological father—whom he never knew—was a Jewish dentist renders this excuse especially poignant. His mother was only seventeen when Truffaut was born; at eighteen, she met Roland Truffaut, whom she married in 1933, and he recognized the boy as his own. Antoine’s uneasy relationship to his adoptive father reflects that of the director. After young François himself committed minor robberies, the senior Truffaut turned him over to the police.

It is not surprising that one of the dominant, although subtle, motifs throughout Truffaut’s work is paternity (nor that his entire career is marked by filial devotion to mentors like Renoir and Hitchcock). In The 400 Blows, the class in English pronunciation revolves around a question that can be articulated only with difficulty: “Where is the father?”—a phrase that resonates both within the film (Antoine has never known his real father) and in the director’s life.

Antoine Doinel became a composite of two compelling individuals, Truffaut and the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. Out of sixty boys who responded to an ad, the director chose the 14-year-old Léaud because “he deeply wanted that role . . . an anti-social loner on the brink of rebellion.” He encouraged the boy to use his own words rather than sticking to the script. The result fulfilled Truffaut’s avowed aim, “not to depict adolescence from the usual viewpoint of sentimental nostalgia, but . . . to show it as the painful experience that it is.”

Anticipating Truffaut’s later preoccupation with the emotional nuances of libidinal love, The 400 Blows is also a tale of sexual awakening: We see Antoine at his mother’s vanity table, toying with her perfume and eyelash curler; later he is fascinated by her legs as she removes her stockings. The stormy relationship of Antoine’s parents—a constant drama of infidelity, resentment, and reconciliation—foreshadows the romantic and marital tribulations of Antoine himself throughout the Doinel cycle, and offers compelling clues to decode the male protagonists of Truffaut’s films in general.

The last shot has been justly celebrated for its ambiguity. This brief but haunting release from the harrowing experiences that fill the movie brings Truffaut’s surrogate self in direct contact with his audience—an intimacy he was to pursue throughout his career. Truffaut’s zoom in to freeze-frame (more arresting in 1959, before this technique became a stock-in-trade of television commercials) provides a mirror image of an earlier shot in the police station. When Antoine is arrested for stealing a typewriter, he is fingerprinted and photographed for the files. The mug shot is in fact a freeze-frame that conveys the definitive and permanent way in which he has been caught.

That The 400 Blows is a record—even an exorcism—of personal experience is first alluded to in Antoine’s scribbling of self-justifying doggerel on the wall while being punished. On a larger scale, we can see the film as Truffaut’s poetic mark on the wall, or his attempt to even the score; by the last scene, the sea washes away Antoine’s footprints as the film “cleans the slate”—although that final image remains indelible.

| Jean-Pierre Léaud | Antoine Doinel |

| Claire Maurier | Gilberte Doinel - la mère d'Antoine |

| Albert Rémy | Julien Doinel |

| Guy Decomble | 'Petite Feuille', the French teacher |

| Patrick Auffay | René |

| Henri Decaë | Cinematography |

| Georges Flamant | Mr. Bigey |

| Daniel Couturier | Betrand Mauricet |

| François Nocher | Un enfant / Child |

| Richard Kanayan | Un enfant / Child |

| Renaud Fontanarosa | Un enfant / Child |

| Michel Girard | Un enfant / Child |

| Serge Moati | Un enfant / Child (as Henry Moati) |

| Bernard Abbou | Un enfant / Child |

| Jean-François Bergouignan | Un enfant / Child |

| Michel Lesignor | Un enfant / Child |

| Luc Andrieux | Le professeur de gym |

| Robert Beauvais | Director of the school |

| Yvonne Claudie | Mme Bigey |

| Marius Laurey | L'inspecteur Cabanel |

| Claude Mansard | Examining Magistrate |

| Jacques Monod | Commissioner |

| Pierre Repp | The English Teacher |

| Henri Virlojeux | Night watchman (as Henri Virlogeux) |

| Jean-Claude Brialy | Man in Street |

| Jeanne Moreau | Woman with dog (as Mademoiselle Jeanne Moreau) |