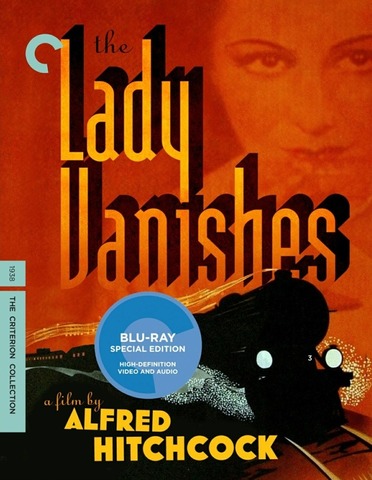

Alfred Hitchcock had hit his early, near-flawless stride by the time of "The Lady Vanishes", the 1938 classic that seems as bright and funny now as the day it was released. After the deliciously comic opening reels at a mittel-European hotel where a train has been snowed in, the plot kicks into gear: a very nice old lady (Dame May Whitty) suddenly disappears in mid-train ride. Worse, the young woman (Margaret Lockwood) who'd befriended her can't find anybody to confirm that the lady ever actually existed. Luckily, suave gadabout Michael Redgrave is at the ready—to say nothing of two English cricket fans, brought to memorable life by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne. The film bops along briskly, borne along on the charm of the players and the witty script by expert craftsman Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat (who also did the delightful "Green for Danger" and the "St. Trinian's" films), to say nothing of Hitchcock's healthy sense of humor about the whole thing—indeed, it may be the most "British" of his films."—Robert Horton"

On the DVD

This two-disc package is the second time "Lady" has been issued by Criterion, and features a (visually and aurally) improved transfer of the film. It retains a commentary from the earlier release, but adds tasty extras: a half-hour documentary from Leonard Leff (standard stuff, but a nice intro to Hitchcockian ideas), plus a 10-minute audio excerpt from Francois Truffaut's legendary book-length interview with Hitch. This is not only a good way to hear Hitchcock on "The Lady Vanishes", it's a fascinating ringside seat at an important moment in film history. And then there's "Crook's Tour", a fun 1941 feature comedy vehicle for Charters and Caldicott, the two characters played by Radford and Wayne (they'd been such a hit in "The Lady Vanishes" that audiences demanded more of them, leading to a long-term teaming in film and radio). All good—but "Lady" itself is the ride you'll be returning to again and again. "—Robert Horton"

THE LADY VANISHES: TEA AND TREACHERY

By Charles Barr

“They can’t possibly do anything to us. We’re British subjects.” One of the delights of The Lady Vanishes is the wit with which it pins down this form of insular mind-set. The passports may say “British,” but these are specifically English people, with not a hint of Welsh or Scottish or Irish, taking the train back home through a politically turbulent Europe in the late 1930s, sitting down to afternoon tea in the dining car punctually at 4:00 p.m. in the English manner. In the film’s series of international encounters, this Englishness is represented admiringly (by the lady of the title, Miss Froy), satirically (by Charters and Caldicott, obsessed with the fortunes of England in cricket and expecting all foreigners to speak their language), and searingly (by the craven Todhunter, whose confidence that “they can’t possibly do anything to us” is followed by humiliation and death).

But while the English-foreign opposition is a dominant structure in the film, there are equally strong oppositions and clashes between the English. “It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him”: George Bernard Shaw wrote this in 1912, in the preface to Pygmalion (and he didn’t intend to exclude women). The encounters among the English in The Lady Vanishes are a set of variations on this theme. Shaw’s play centers on differences in accent and on the class distinctions they represent, and class is a likewise dominant theme in Hitchcock’s film, the basis of the savage behavior that underlies its comedic surface.

Meeting Hitchcock in Hollywood a few years after The Lady Vanishes, John Houseman found him to be “a man of exaggeratedly delicate sensibilities, marked by . . . the scars from a social system against which he was in perpetual revolt and which had left him suspicious and vulnerable, alternately docile and defiant.” The son of a tradesman, Hitchcock was exposed to the subtle brutalities of the English class system from an early age, both in his own education and as a precocious London theatergoer fascinated by the work of such anatomists of English society as Shaw and John Galsworthy. Like any British filmmaker of the period, he could hardly have avoided class issues when he began as a director in 1926, and his films show a consistent sharpness in handling them, in particular the tensions created by relationships across a class divide, as in the silent films The Lodger (1927) and The Manxman (1929) and the early sound films Murder! (1930) and The Skin Game (1931). The latter, from a play by Galsworthy, offers the most savage representation of class hostility in all of Hitchcock’s films, through the depiction of the vicious enmity between a family of old money, the Hillcrists, and one of new money, the Hornblowers. The class analysis in the first five films in the director’s celebrated thriller sextet is more oblique, partly because of the use of several non-English protagonists, including Canadian Richard Hannay in The 39 Steps; in The Lady Vanishes, his penultimate film before leaving for Hollywood, it’s as if he has saved up all the sensitivities and resentments noted by Houseman and worked them organically into the story, perhaps with Galsworthy in mind and certainly with the dazzling assistance of his new screenwriters, Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat, and a cast that is ideal in every particular.

Key distinctions are laid out with superb economy in the early hotel scenes that precede the train journey. The idle upper class of Charters and Caldicott and the new money of Iris Henderson and her friends despise each other at first sight. Iris is returning by train to get comfortably married to Lord Charles Fotheringale, mainly, it seems, because “Father’s simply aching to have a coat of arms on the jam label”; her companions raise a glass to her and “to the blue-blooded check chaser she’s dashing to London to marry.” A perfectly cynical class alliance between money and title is thus sketched out. The patrician lawyer Todhunter is desperate to protect his status at all costs and refuses all contact with his inferiors. While the train speeds Iris back toward her loveless marriage, her attempt to solve the mystery of Miss Froy’s disappearance is blocked by the obstinate intransigence of her countrymen, working in unconscious collaboration with the forces of European fascism that have kidnapped her.

Clearly, this gave the film an especially potent meaning for the England of 1938, a time when the ruling classes were still working to appease Hitler and a class-stratified country was patently unready to pull together effectively if war should nonetheless become unavoidable. The native cinema’s habitual concern with class became even more focused at this time, whether in obsessive celebration of the system, as in Goodbye Mr. Chips (1939), or in the sharper analysis of Shaw. Pygmalion itself was filmed in 1938 and had its London premiere in October, exactly one day before The Lady Vanishes, and the two were revived together soon afterward in a peculiarly felicitous double bill. Unashamedly schematic and didactic, Pygmalion foregrounds its theme of the hierarchies of accent and the class system; The Lady Vanishes enacts them, plays them out, in a triumphant comedy-adventure that, in the words of Philip French, “comes up dazzlingly fresh every time.” At the climax, the characters fight their way out of the morass of snobbery. The worst offender dies; the cricketing drones are shocked into good sense. A new character, introduced on the train as a foreign nun in the service of the fascists, turns out to be a civilian Englishwoman and weighs in heroically; no one even remarks on her lower-class London accent. And Iris, at the last, abandons Charles for Gilbert, unraveling the deal between money and title that was so carefully set up.

Gilbert’s own class status is quite hard to read, because, like Miss Froy, he never flaunts or discusses it, but he seems, also like her, from his voice and manner and from what we infer about his background, to belong slightly above the middle of the middle class. Her governess role would have been one of the few respectable employments open to an independent woman; he remains unbothered by his family’s recent material decline. What is crucial is that neither of them is in the business of hating or despising anyone else, whether English or foreign, on sight or on hearing them talk, and we can rejoice unreservedly in Iris’s final embrace of them both. In the last triumphant resistance on the train, class differences have not been set aside, far from it, but they no longer get in the way. This vision of hard-won solidarity is what made The Lady Vanishes such a salutary film for the England of its time, and it is integral to its unfading status as a great fable of Englishness, the dark side and the light.

THE LADY VANISHES: ALL ABOARD!

By Geoffrey O’Brien

The Lady Vanishes (1938) is the film that best exemplifies Alfred Hitchcock’s often-asserted desire to offer audiences not a slice of life but a slice of cake. Even Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer, in their pioneering study of Hitchcock, for once abandoned the search for hidden meanings and—though rating it “an excellent English film, an excellent Hitchcock film”—decided it was one that “requires little commentary,” while François Truffaut declared that every time he tried to study the film’s trick shots and camera movements, he became too absorbed in the plot to notice them. Perhaps they were disarmed by pleasure, The Lady Vanishes being as pure a pleasure as the movies have offered; the ever-spirited Miss Froy, not long before she vanishes, remarks that her name “rhymes with joy,” and indeed, the whole film breathes an air of delight like nothing else in Hitchcock. The central situation—the disappearance of a woman whose very existence is subsequently denied by everyone but the protagonist—may seem to provide the perfect matrix for the kind of paranoid melodrama that would proliferate a few years later, in the forties, in films like Phantom Lady, Gaslight, and My Name Is Julia Ross, but here the dark shadows of conspiracy are countered by a brightness and brilliance of tone almost Mozartean in its equanimity. Most of the time we are too exhilarated to be frightened.

The film arose in a more accidental way than was customary with Hitchcock. In 1937, he was at a turning point in his career. After making his way to the forefront of the British film industry with works like The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The 39 Steps (1935), he was involved in negotiations with David Selznick that would soon take him to Hollywood. Still under contract to Gaumont British, however, and at loose ends for a script, he reached for a project already developed and in fact nearly filmed a year earlier by the American director Roy William Neill. Though Hitchcock and his wife, Alma Reville, made significant adjustments (notably with regard to the early hotel scenes and the final shoot-out), the script (freely adapted from the novel The Wheel Spins, a rather unthrilling thriller by Ethel Lina White) is very much the work of the brilliant screenwriting team of Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, to whom especially can be credited the verbal richness of the comedy, whether it’s Miss Froy busying herself with “a most intriguing acrostic in The Needlewoman” or Basil Radford’s Charters expostulating, “After all, people don’t go about tying up nuns!” (With Hitchcock gone to America, it would be left to Gilliat and Launder—as writers, directors, and producers—to keep up something of that mix of wit and thrills on the home front.)

The cozy claustrophobia of the film, as it moves from overcrowded hotel to tightly packed train compartment, reflects the circumstances of the budget-conscious British film industry of the time (constraints under which Hitchcock had honed his skills). It was shot, according to Hitchcock, “on a set ninety feet long. We used one coach; all the rest were transparencies or miniatures.” A reassuring sense of smallness of scale is instilled by the opening panorama of a snowbound toy train station in the remote Balkan enclave of Bandrika, “one of Europe’s few undiscovered corners”; Hitchcock might still be the little boy whose hobby was collecting train schedules from around the world. A hint of giddiness at the harmlessness of it all demonstrates from the start that we are in a world created by movies—the same world explored by Lubitsch comedies and Astaire and Rogers musicals—in which the worst things that can happen are the minor discomforts and embarrassments of travel.

Along with those discomforts comes a muted but pervasive erotic charge, taking a variety of forms: the comic byplay of the blinkered cricket fans Caldicott and Charters (with the wonderful team of Naunton Wayne and Radford unavoidably evoking Laurel and Hardy), forced to stay in the maid’s room and unnerved by the least hint of sexuality; the suggestive exchanges of the adulterous couple Mr. and “Mrs.” Todhunter (as the titles coyly put it), whose once passionate affair is already cooling; the trio of irresistible young English girls, Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood) and her friends, who for a moment seem to have stepped out of the chorus line of a Busby Berkeley musical. It needs only the midnight meeting of Iris and the rugged young folklorist Gilbert (Michael Redgrave)—as, in a scene straight out of Top Hat, she’s kept awake by his reenactment of a Balkan wedding dance on the floor above—to set in motion a robustly amusing comedy of courtship.

The mood is frankly sexy in a way that would never really be matched in Hitchcock’s American films, where even the most impassioned exchanges (Bergman and Grant’s protracted kiss in Notorious, for example) seem too carefully planned to allow much room for spontaneity. Lockwood and Redgrave, by contrast, really do seem like young people who have just met and who, despite their bumpy introduction, can’t wait to run off together. (When they finally find themselves alone in a cab at the end, the relief is palpable.) The film may be not simply a farewell to England but a farewell to youth, by a director about to turn forty. We never forget that these are young people still somewhat on the margins of the grown-up world, with Lockwood rushing too quickly into well-appointed adulthood by way of marrying the wrong man, and Redgrave lingering maybe a bit too long in uncommitted, footloose world roving—a forecast, perhaps, of the Grace Kelly–James Stewart couple in Rear Window, but in a younger and less neurotic mode.

It isn’t until twenty-four minutes into the film that the first dark note of Hitchcockian menace intrudes, in the abrupt strangling of an apparently harmless serenader. Thereafter, the plot takes over in a stunningly swift exposition. From the moment the heroine—concussed by a fallen planter intended for Miss Froy—comes to in her train compartment to confront her oddly assorted fellow passengers, we are in the grip of a narrative rhythm of incomparable assurance. In a very few minutes, we have lived the episode of her tea break with Miss Froy, in which Dame May Whitty reinforces the impression, already created by her scene with the hapless cricket fans the night before, that she is the most perfectly harmless of English ladies, a mildly eccentric governess given to poetic fantasies about snowbound mountains but rigorous when it comes to the preparation of her tea. Since in a moment she is going to vanish, Miss Froy must for a moment dominate everything, and Whitty achieves just that, and even more: she makes us feel an affection for Miss Froy deep enough that her disappearance will seem an unspeakable affront, an assault on Englishness itself in its least threatening form.

The pivotal point is the exchange, back in their compartment, of close-ups of Whitty and Lockwood, as the former hums the haunting melody sung first by the strangled balladeer and the latter drifts off into a sleep whose duration is represented by a montage of wheels, wires, and railroad tracks. She will come to for the second time in a radically altered reality in which nothing can be relied on. The intimacy of that last exchange of glances between the two women has a poignancy that infuses all that follows: the scenes of Lockwood and Redgrave relentlessly searching up and down the train’s corridors; the introduction of the psychiatrist Dr. Hartz (Paul Lukas), with his suavely enunciated theories of hallucination; the rapidly shifting scenes of denial and concealment and substitution.

Finally, at nearly the exact midpoint of the film, the momentary reemergence of Miss Froy’s name, spelled out on the dusty window of the dining car (an apparition beautifully timed in both its appearances and disappearance), precipitates a crisis for Lockwood, as she realizes that not even Redgrave believes her. It is a moment rich in Hitchcockian resonances. In her despairing outburst—“Why don’t you do something before it’s too late?”—we catch a glimpse of future and more painfully depicted moments: Teresa Wright in 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt exploding under the pressure of her secret knowledge of her uncle’s guilt, Doris Day in 1956’s The Man Who Knew Too Much screaming as she is forced to choose between saving a stranger’s life and risking her son’s, Vera Miles in that same year’s The Wrong Man slipping into madness in the wake of her husband’s wrongful incrimination.

But Margaret Lockwood here is the freshest and least damaged of Hitchcock heroines, and what comes through is not so much her despair as her determination to get to the bottom of things despite all opposition. Her insistence on the reality of what she has seen is the only sure guide through a labyrinth of false impressions, even as the insidious Dr. Hartz tries to convince her that the vanished Miss Froy is “merely a vivid subjective image.” The whole train, for that matter, is a congeries of vivid subjective images, from the magician’s rabbits peering up out of a top hat at a violent struggle in the baggage car to the nun in high heels keeping guard over an accident victim wrapped up like a mummy. This Europe of sinister baronesses and grinning conjurers is indeed a runaway train bound for nowhere good.

All along, the film pits England against the world, with the English characters not necessarily getting the best of it. The loathsome adulterer Todhunter (Cecil Parker at his most unctuous) is the very picture of moral indifference, and only Whitty and Redgrave show much interest, however condescending, in the customs of foreigners. Wayne and Radford, as the cricket fans desperate to get back in time for the match, effortlessly steal the film with their running display of blithe bafflement at all things foreign. But a film that mocks British insularity and hypocrisy ends as a celebration of British pluck and solidarity, as every British character (except for the cowardly appeaser Todhunter, shot down waving a white flag) finally reveals a courageous nature: the sinister nun is really just a good English girl gone astray, and the complacent cricket fans turn out when the chips are down to be dead shots with nerves of steel. Even Dr. Hartz—the most genial of villains—is forced in the end to wish them “jolly good luck.” The whole climactic episode is a send-up of Boy’s Own heroics—except that the blood on Radford’s hand is all too real. The dreadful shock on his previously imperturbable face is like a harbinger of the real danger with which the film has finally, unavoidably, made contact.

Back in the days when Hitchcock’s American films were usually regarded as a falling off, The Lady Vanishes was the picture that critics often used as a measuring rod for berating his subsequent output—lamenting the loss of its sharp wit, its free invention, its nimble pace and lighter-than-air frothiness—as if it were a token of the kind of work he might have continued to turn out had he remained in his native land. But given that the year was 1938, it seems unlikely that the mood of The Lady Vanishes could have been easily sustained or repeated. This was a bubble of its moment—the assertion of a fairy-tale triumph of humor and youthful energy over the darkest forces of Central European evil—realized at nearly the last moment such a bubble was possible. We can watch it over and over just as children can hear the same fairy tale again and again, marveling that such serenity and playfulness could flourish even on the brink of an abyss.

CHEZ DU CINEMA: THE LADY VANISHES

By Ron Deutsch

Sir Alfred Hitchcock once said, “I’m not a heavy eater. I’m just heavy, and I eat.”

Hitchcock’s father was a grocer, so we can assume young Alfie grew up knowing his way around food. His films are filled with food and eating motifs, from the kitchen murder in Sabotage to the exotic dinner menus in Frenzy.

I just taught a class on 1963’s The Birds here in Austin, and in preparing for it, I came across stories its screenwriter, Evan Hunter (a.k.a. Ed McBain), had told about having dinner at the Hitchcocks’, which was considered quite the honor in Tinseltown. Alma, Hitchcock’s wife, cooked, and Sir Alfred would handpick bottles from his wine cellar and regale his guests with entertaining and often macabre tales. But it wasn’t always like that. Alma, who was always more than just a wife—she was also Hitch’s collaborator and confidante—took up cooking only after the couple moved their household to Hollywood after The Lady Vanishes’ release to make 1940’s Rebecca; once there, their cook was inspired to quit (to become a chiropractor, of all things).

“With only cookbooks for a script, she memorized and executed my dishes to such perfection that there’s been no need to hire more than an understudy for the role,” Hitch wrote of his wife in McCall’s magazine in 1956. “I would pit Alma against a chef in any of the finest restaurants. She can prepare a meal perfectly and completely—except trample the grapes for the wine, and I’d rather she didn’t do that, really. The French need the business.”

“We’re both fond of French cooking,” he confided, “and Alma duplicates my own eating habits. When I go on a diet, which I often do, Alma faithfully loses weight with me, although she’s not quite five feet and weighs less than 100 pounds. Contrary to what one might think from my measurements . . . I’m simply one of those unfortunates who can accidentally swallow a cashew nut and put on thirty pounds right away.”

Elsewhere, he explained, “Most people think a gourmet is a food lover who tucks in his napkin and starts eating fine food. I’m a theoretical gourmet. I’m really more interested in the acquisition of hard-to-find foods than in eating them. We have oysters flown in from England each September, and we savor Pauillac. That’s milk-fed lamb that’s never fed on grass. We roast it lightly to keep it moist and tender.”

But he was also famously forthright about one food he disliked—and I’m putting that mildly. “I’ve never eaten an egg in my entire life,” he once admitted to columnist Johna Blinn. “An egg cooked by itself, that is. And I can’t stand the smell of a hard-boiled egg.”

We should note, though, that Hitchcock had no problem eating dishes that contained egg. In fact, he submitted a recipe for quiche lorraine to several celebrity cookbooks (actually, two different recipes—something to discuss another day, I’m afraid).

To Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, the director said, “I’m frightened of eggs, worse than frightened, they revolt me. That white round thing without any holes . . . Brrr! Have you ever seen anything more revolting than an egg yolk breaking and spilling its yellow liquid? Blood is jolly, red. But egg yolk is yellow, revolting. I’ve never tasted it. And then, I’m frightened of my own movies. I never go to see them. I don’t know how people can bear to watch my movies.”

Joking aside, he seemed never to tire of the subject. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, he ranted, “Oh, I really do [hate eggs]. I think the smell of a hard-boiled egg is the most horrible thing in the world. How people can eat them! I knew a very big man—he was a theatrical producer—and we used to have lunch together; the hors d’oeuvre trolley would go by and, without the trolley stopping, he’d stretch a hand out, pick up a hard-boiled, and pop it into his mouth. Oh, really, it was most revolting. Had he popped a sardine or something—that would have been different. But an egg!”

This fear of eggs may well be from whence his famous story device, the Egg MacGuffin, comes from. (Please don’t hate me for that.)

The Lady Vanishes is truly one of Hitchcock’s greatest films. It’s fun, it’s sweet, and it holds up more than seventy years after its release, not just as an engaging and romantic adventure but as a standard to which films of its type have to live up to even today. There’s not much food, per se, in the picture. The dining room in the small Balkan hotel is all out of food when the bumbling Brits Charters and Caldicott sit down to eat, except for some cheese and pickles the vanishing lady herself, Miss Froy, shares with them. Meanwhile, Margaret Lockwood’s character and her friends have “some chicken and a magnum of champagne” brought to their room. And while there are several scenes in the dining car of the train, we don’t really glimpse what the passengers are eating, except for Michael Redgrave’s soup. Then, of course, there’s Harriman’s Herbal Tea—“a million Mexicans drink it!” Sadly, and not just for the legions of thirsty Mexicans, there is no such product in real life.

The Hitchcocks’ daughter, Patricia, wrote a biography of her mother, and in it she shares recipes from the Hitchcock kitchen. I decided to pair the film with one of those, something fun and sweet, engaging to the senses, romantic . . . and made with eggs.

Crêpes Elizabeth

Adapted from a recipe in Alma Hitchcock: The Woman Behind the Man, by Pat Hitchcock-O’Donnell and Laurent Bouzereau

Makes 10–12

1⅛ cups all-purpose flour

4 tablespoons sugar

1 pinch salt

3 large eggs

1½ cups milk

1 tablespoon butter, melted, plus more for frying

1 tablespoon kirsch (cherry brandy)

15–20 strawberries (depending on size), sliced or diced

sugar for sprinkling

2 tablespoons slivered blanched almonds (Alma suggests shredding and buttering whole blanched almonds, but I got lazy on this step)

Whipped cream or ice cream

Combine flour, sugar, and salt in a mixing bowl. In a separate bowl, beat the eggs lightly. Whisk in the milk. Slowly add the eggs and milk to the dry ingredients while whisking. Whisk until the batter becomes smooth (according to Alma, “It should coat a spoon. If it is too thick, stir in a little more milk.”). Add the tablespoon of melted butter and the kirsch and stir to combine. Let the batter stand at room temperature for an hour or two.

Heat an eight-inch frying pan over a medium flame, then add about two teaspoons of butter and swirl the pan to coat it. Add ¼ cup of batter and swirl that around too. Using a spatula, keep the crêpe from sticking to the sides of the pan and check on its underside. As soon as you start to see some browning, gently and carefully flip the crêpe. When the second side is done, remove the crêpe to a plate. (Expect to mess up at least one or two in the beginning before you get the hang of it.) For the rest of the crêpes, you should need to add only about ½ teaspoon of butter to the pan between frying.

Butter a shallow ovenproof dish or pan. Turn on the oven’s broiler.

Using about two tablespoons of the strawberries, place them in a row across a crêpe, a little to one side of the center. Sprinkle sugar (to taste) on the strawberries. Gently roll up each crêpe and place it in the buttered pan. Sprinkle the crêpes with the almonds. Place the pan under the broiler, just until “the crêpes blister.”

Serve with whipped cream or ice cream.

Ron Deutsch also blogs at chefducinema.com.

| Margaret Lockwood | Iris Henderson |

| Michael Redgrave | Gilbert |

| Paul Lukas | Dr Hartz |

| Dame May Whitty | Miss Froy |

| Cecil Parker | Mr Todhunter |

| Linden Travers | "Mrs" Todhunter |

| Nauton Wayne | Caldicott |

| Basil Radford | Charters |

| Mary Clare | Baroness |

| Emil Boreo | Hotel Manager |

| Googie Withers | Blanche |

| Sally Stewart | Julie |

| Philip Leaver | Signor Doppo |

| Zelma Vas Dias | Signora Doppo |

| Catherine Lacy | Nun |

| Josephine Wilson | Madame Kummer |

| Charles Oliver | Officer |

| Kathleen Tremaine | Anna |

| Sidney Gilliat | Screenplay |

| Frank Launder | Screenplay |

| Alma Reville | Continuity |

| Jack Cox | Photography |

| R.E. Dearing | Editing |

| Roy Ward Baker | Assistant Director |

| Alfred Roome | Cutting |

| Sydney Wiles | recording |

| Alex Vetchinsky | Settings |

| Albert Whitlock | scenic artist |

| Louis Levy | Musical Director |

| Ethel Lina White | Author of "The Wheel Spins" Original Novel |